The following was written in 2014, upon the 30th anniversary of the Feed the Hungry San Miguel.

Feed the Hungry and Nutrition: The Story of the Plato del Bien Comer

By Dianne Walta Hart

In front of the crowd of 50 people, Diana Rodríguez Rodríguez commanded everyone’s attention. She crisscrossed the room and talked lickety-split fast. She had a lot to explain in this classroom in a rural village, an hour from San Miguel de Allende, as she clarified changes in nutrition. The audience, comprised of parents of the kindergarten and primary school children, had their eyes glued on her.

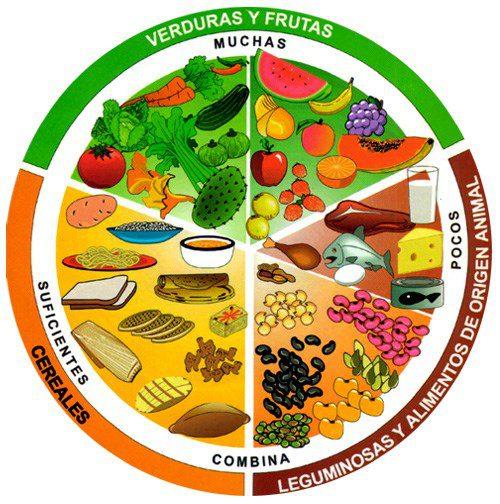

Olivia Muñíz Rodríguez, Feed the Hungry San Miguel’s program director, had warmed up the crowd by reminding them what Feed the Hungry does: it feeds their children nutritious meals every school day. Olivia had explained that in many parts of the world, the food pyramid has changed and the new one – now a plate – colorfully illustrates the variety of nutritional foods to eat by showing what to eat less of and what to eat more of in order to have a healthy diet. She and Diana were there to explain this change as it relates to the traditional Mexican diet; they were going to teach the parents and then evaluate the health of the children.

When it was Diana’s turn, she selected a mother from the audience and asked her name. Next she asked how many children she had, their ages, and followed with the big question: “What do they eat for breakfast?” Before the woman could answer, Diana let forth her joking command, “dígame la verdad, don’t lie to me.” The audience, mostly women dressed in baseball hats, jeans, sweats, rebozos, and dusty shoes, burst into laughter. Diana had them. It was obvious that they all had been pondering how much of the truth to tell her.

“Bread, jam, and orange juice,” the woman said. Others yelled out, “milk and Galletas Marías,” a mildly sweet cookie that is almost a staple in the Mexican diet. Others added, “soup with rice and nopales,” followed by many frijoles, tortillas, and lentejas (lentils).

Diana has her license in Nutrition and Food Science. Born in Celaya, she has lived in San Miguel de Allende most of her life. She studied at the Universidad Iberoamericana in León. At Leon’s IMSS hospital, she did her clinical work by evaluating patients and developing specific diets according to their needs. Now, working with Feed the Hungry San Miguel since 2010, she’s convincing the parents to feed their children more fruit and vegetables and to cut back on the beans, rice, and tortillas. To, in fact, change the traditional diet to one that would be more nutritious.

With her big smile and humor, she asked the parents how many times a day they say to their children, “Would you like more rice?” Lots of laughter followed. “Another tortilla?” The parents laughed again and nodded. Then Diana became serious, “If you give them five Galletas Marías a day, then don’t give them any rice.” That quieted the crowd. Diana pointed to the Plato del Bien Comer, the new version of the old food pyramid, and asked, “How many tortillas should people eat every day?”

What followed next can only be described as controlled pandemonium with all 50 parents talking to their friends and neighbors. When they settled down, Diana told them that primary school students should have no more than six tortillas a day and kindergarteners no more than four or five. The shock settled in. Obviously that amount was well below what their children were used to eating. Next she showed them how they could accomplish this within their limited budgets by buying fewer of some items and more of others. Feed the Hungry has a family garden program, she told them, urging them to sign up and start growing their own vegetables.

Diana explained that she and Olivia will have follow-up visits during which they will measure the children. After the evaluations, she’ll either congratulate the parents on their good nutritional work or speak to them about their children’s less-than-ideal health. If the diagnosis is serious, the parents have an obligation to do something.

Some weeks later, after Diana and Olivia had evaluated the students, they returned to the rural classroom, this time to an empty room that provided privacy for the parents. Diana flipped open her laptop and called the mothers in, one by one. The women were aware that they had been contacted because their children were declared at risk based on their body mass index (BMI). The BMI provides a reliable indicator of body fat based on age, gender, height, and weight and is used to screen for health issues that may be pre-existing or that may lead to future problems, such as diabetes and heart disease. Although the women were apprehensive, they knew that Diana was there to help them.

The first one, dressed in many shades of pink from her socks to her sweatshirt, smiled tentatively as she pulled up a little child’s desk across from Diana’s equally small one. Looking directly at the woman, Diana asked, “How does your child seem to you?” The woman shrugged and said, “She doesn’t eat much, doesn’t like much.” Then Diana delivered the bad news. She told her that her daughter is severely malnourished. Not only was this evident through the BMI measurement, but Diana had noticed the child’s dry cracked skin, hair streaked with different colors, and her lifeless demeanor. The woman nodded but continued to smile self-consciously.

“I’ll give you some tips. One, tell your daughter she has an illness,” Diana said, as she leaned across the small desk. “Two,” she tapped her fingernails, “instead of the ten tortillas she eats every day, look at our Plato del Bien Comer.” Then Diana whipped out the laminated sheet of El Plato del Bien Comer and reviewed with the mother what her child should be eating. “Tortillas are not nutritious. No more than four a day.” Diana’s third tip was explaining how the whole family needed to eat and told her that she’ll be back to talk in a few months. “Let’s see some change by then.”

The next woman appeared to be nervous, so Diana smiled and joked until the woman relaxed. “Can you read?” “Un poquito,” the woman answered. Out came the now familiar Plato del Bien Comer, its colorful drawings more realistic to the woman than any long list of words could ever be. The mother admitted that her son, although not grossly overweight, drinks too much Coca Cola and eats 18 tortillas a day. Diana suggested lowering those amounts little by little over time and imitated a child pleading for more food. The mother laughed and promised to do as Diana suggested.

The next case was equally serious. The second grade girl was 12 kilos overweight and the heaviest child in school, so much so that other students teased her. The mother is diabetic, and both the mother and father are heavy. Diana advised the woman, who cannot read, about dietary changes that could be made. “Exercise with her,” suggested Diana, “and if you walk with her, make sure she walks faster. Make a game out of the exercise.”

The shyest mother kept her hand over her mouth for the first part of the interview. The single mother of an only child in the first grade, she is unemployed and relies on occasional economic help from her brother. Diana recommended that the daughter, four kilos underweight, ask the Feed the Hungry cooks for more than one serving. “Make sure she eats everything at school and tell her that she can ask for more.” The mother’s hand finally dropped down to her lap as she kept her eyes on Diana, who explained how the woman could manage economically. Diana prefaced many of her sentences with “when you can” and “when you have the money,” giving the woman confidence in her ability to help her child. By the end, this single mother was smiling, knowing she had help in the struggle to keep her daughter healthy.

Making them healthy, that’s what Feed the Hungry San Miguel de Allende is all about. It’s feeding the children, it’s growing the food, and it’s guiding the parents and children.